modeling CRDTs in Alloy - introduction and the importance of idempotence

Brian Hicks, October 9, 2023

I've been interested in local-first software for a long time, and recently attended an event about it with a bunch of luminaries from various research groups. I learned a lot, and it rekindled my interest in syncable data structures.

I've tried to sync data over the years with varying degrees of success. For example, I've known about operational transformations (OT) for a while (via Quill, but I have never been able to get the syncing operations working to my satisfaction. Message ordering is crucially important in OT, and it's hard to get right. I get the impression that the engineers who worked on Google Wave (which also used OT) also struggled with this. One of them (Joseph Gentle) was quoted as saying "Unfortunately, implementing OT sucks. There's a million algorithms with different tradeoffs, mostly trapped in academic papers. […] Wave took 2 years to write and if we rewrote it today, it would take almost as long to write a second time." (Worth noting that he later said it might not take as long today, but still… pain!)

In contrast to OT, conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) seem really promising! Wikipedia has a good summary, which I'll quote:

In distributed computing, a conflict-free replicated data type (CRDT) is a data structure that is replicated across multiple computers in a network, with the following features:

- The application can update any replica independently, concurrently and without coordinating with other replicas.

- An algorithm (itself part of the data type) automatically resolves any inconsistencies that might occur.

- Although replicas may have different state at any particular point in time, they are guaranteed to eventually converge.

These properties appeal to me! If CRDTs can automatically and independently converge, no matter how far apart they drift, then you could store them wherever and however you like. Offline support should be simple, and adding live collaboration features should not mean spending years figuring out edge cases. Sign me up!

What are CRDTs made from, though? It looks like typically it's some internal stuff, a function to resolve the internal stuff to a value, and a function to merge two of the data structure together. The merge function is the number-one-most-important thing about this whole arrangement, and has to satisfy these three laws:

- commutative (so

merge(a, b) must be the same as merge(b, a)) - associative (so

merge(merge(a, b), c) must be the same as merge(a, merge(b, c))) - idempotent (so

merge(a, b) must be the same as merge(merge(a, b), b).)

If all these are true, we can always merge two states, regardless of how many changes have been made since we last merged, and get the same result on both sides of the sync. Cool!

These seem like the kinds of things that Alloy would be good at modeling, so let's try it! Over the next couple of posts, I'm going to build a handful of data structures that follow these three rules and compose them into data structures we could build an application on top of.

Let's get a taste for this with OR(bool, bool). First off, does it satisfy our three properties?

- commutative:

OR(True, False) is the same as OR(False, True) - associative:

OR(OR(True, False), True) is the same as OR(True, OR(False, True)) - idempotent: calling

OR(x, True) gives the same result as OR(OR(x, True), True).

So it looks like OR might be fine, but let's be sure. We can check this in Alloy by first defining a boolean:

enum Bool { True, False }

Then a merge function, which we check is correct:

fun merge[a, b: Bool]: Bool {

// OR

a = True implies a else b

}

check MergeIsCorrect {

// read as: given `a` and `b`, which are `Bool`, the

// following condition must hold.

all a, b: Bool |

(a = True or b = True) implies merge[a, b] = True

}

And finally, our three properties:

check MergeIsCommutative {

all a, b: Bool | merge[a, b] = merge[b, a]

}

check MergeIsAssociative {

all a, b, c: Bool | merge[merge[a, b], c] = merge[a, merge[b, c]]

}

check MergeIsIdempotent {

all a, b: Bool | merge[a, b] = merge[merge[a, b], b]

}

Great! Alloy can't find any errors with OR. We expected that, so let's break it in interesting ways. What if the merge function was XOR(bool, bool) instead?

fun merge[a, b: Bool]: Bool {

a = b implies False else True

}

Now Alloy finds that we've broken idempotency: merge[False, True] is True, but merge[merge[False, True], True] is False. This would cause big problems if we used XOR as a merge function: the act of syncing could change our values! We can imagine this sequence of events:

- Node A sets the value to

True - Node B sets the value to

False - The nodes sync, both resolving to

True (since XOR(True, False) is True) - The nodes sync again, both resolving to

False (since XOR(True, True) is False) - Further syncs would stay at

False until someone changed the value to True, at which point we'd repeat from step 3.

But in a fun twist of fate, we don't have to imagine this; we can ask Alloy to generate these traces for us. First we'll make a document that contains a changeable value:

sig Document {

var value: one Bool,

}

Then we'll define a not for our boolean and a couple of operations (flipping an arbitrary value and syncing two documents):

fun bool_not[b: Bool]: Bool {

b = True implies False else True

}

// intent: when `flip` is true, the provided document will go

// from True to False or False to True in the next time step.

// This serves as our proxy for someone clicking a button in

// a UI or whatever.

pred flip[d: Document] {

// implementation: `value` is actually a set of tuples from

// documents to booleans, and `value'` is the same but in the

// next time step. We set the entire value explicitly

// (instead of just saying like `d'.value = False`) because

// otherwise Alloy could say "and what if something changes

// that you weren't expecting?"

//

// Syntax: `->` creates a tuple, and `++` replaces all

// existing tuples referencing `d` in the set.

value' = value ++ d->bool_not[d.value]

}

// intent: merge two documents together in a way that all the

// `merge` rules hold. Maybe imagine we have `d1` locally and

// are getting `d2` over the network (but remember that order

// should not matter!)

pred sync[d1, d2: Document] {

let merged = merge[d1.value, d2.value] {

value' = value ++ (d1->merged + d2->merged)

}

}

Now wire them up so these events can happen over time:

pred init {

// `Document` is a set of documents, and `->` will apply pairwise

// for the sets in its arguments, so this means this says "all

// documents start at `False`"

value = Document -> False

}

fact traces {

// this says "start with `init`, then pick one of these things to

// happen at each time step." Putting it in a `fact` means that

// any assertions we make from now on assume that we want these

// instructions.

init

always {

(one d: Document | flip[d])

or (some d1, d2: Document | sync[d1, d2])

}

}

We can now check that our sync is idempotent:

check SyncIsIdempotent {

// at all times, if sync happens twice in a row (the `;` syntax) then

// the next value (`value'`) and the one after that (`value''`) should

// be the same.

always all d1, d2: Document |

(sync[d1, d2]; sync[d1, d2]) implies value' = value''

}

If we make OR our merge function, this works fine and Alloy can't find any counterexamples. If we use XOR for merge, though, Alloy finds the trace I mentioned could show up earlier. Here's what it shows us.

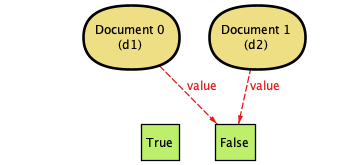

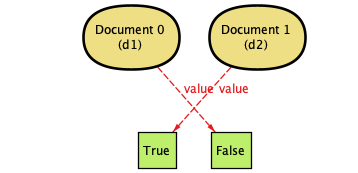

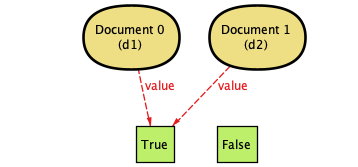

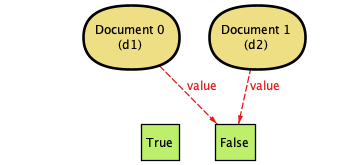

| Step | Description | Image |

|---|

| 1. | We start off with all documents at False. |  |

| 2. | One of the documents flips to True. |  |

| 3. | The documents sync, converging to True. |  |

| 4. | The documents sync again, converging to False because XOR(True, True) (the previously synced state) is False. |  |

| 5. | Stay here forever or return to 2. | |

In case you're encountering them for the first time, these diagrams are generated by Alloy—they're pretty fantastic for showing other people exactly what can happen in a system. (That's also why Document 0 is d1 and so on. The documents are defined separately, and the d1 and d2 labels come from our check so we can see what's doing what.)

Alloy can do more than this, too. If we modify our condition to have 3 distinct documents like this:

check SyncIsIdempotent {

always all disj d1, d2, d3: Document |

(sync[d1, d2]; sync[d2, d3]) implies value' = value''

}

Then Alloy shows the situation getting even sillier. You only need one of the nodes to be False, at which point it's possible that the documents as a whole could never converge again and just flap back and forth randomly forever. It all depends on which documents sync with which other documents. Turns out idempotency is pretty important!

That's it for today. Next time we'll go from booleans-of-dubious-usefulness to counters!

Big thanks to Jake Lazaroff for his help reviewing this post. If you're interested in this stuff, he also recently published an interactive intro to CRDTs that you may enjoy!