Modeling Database Tables in Alloy

Brian Hicks, January 2, 2023

Formal methods tools like Alloy are not just for proving correctness properties in distributed systems (or whatever) but can be a useful tool for mere mortals like me! As I mentioned previously, I've been using Alloy to help me avoid data modeling mistakes before they're encoded in hard-to-change places, like database schemas. In this post, I'll show my thought process as I use Alloy to model the schema for a project for my makerspace, including some of the mistakes that Alloy helped me avoid.

I joined the Inventor Forge Makerspace recently to get access to some better tools for home recycling. There are some cool tools there (Lasers! CNC machines! Plasma cutters!) that need both special training and have high demand among the folks who use the space. Right now, we use a shared Google calendar to schedule time on different machines. Unfortunately, I don't have a personal Google account, so it's harder to schedule than I'd like! There are a couple of other people in this situation too, so I'm in the process of building a tool to track training and scheduling.

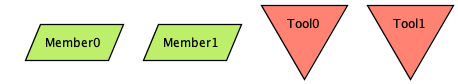

We'll start by modeling Member (someone who can join the makerspace) and a Tool (something that we need training and scheduling for.) We'll use Alloy's basic building block of sigs for this. If you haven't been exposed to Alloy before, you can think of sigs as sets that can contain values (like rows in a database table.) So you can think of Member as the set of all members of the makerspace, which can contain values like Member0 and Member1.

sig Member {}

sig Tool {}

We can ask Alloy to generate examples for this small model. They won't be super useful at this point—we haven't modeled any interactions between Member and Tool—but they let us get a sense of what Alloy can provide us. For example, here's an instance with two members and two tools:

We can ask Alloy for any number of instances, and we'll be looking at these frequently to find the kinds of edge cases we're interested in.

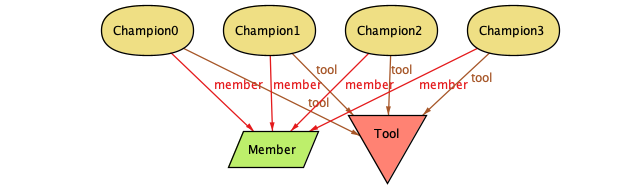

To get authorization to use a tool at my makerspace, you need to contact a "tool champion" who is responsible for doing safety training. (They're not just "trainers" because they also maintain, fix, and upgrade the tools.) In our model, we'll first connect Member and Tool by adding a new sig Champion, which has a relationship with both.

sig Champion {

tool: one Tool,

member: one Member,

}

When we're turning this model into a real database, Champion will become a champions table, with foreign keys to tools (tool_id) and members (member_id.)

Now that we have some relationships, we can poke around in the instances Alloy generates to see if we can find anything that feels off. For example, Alloy shows that we're allowing duplicate champions for the same member and tool:

This could cause us problems later. Imagine what could happen if we also had a boolean field named active and a champion resigned. We could end up with one row that says they're active and another that says they're inactive. We'd have to define some conflict semantics in the application, making sure to only change the one we care most about, or all of them, or whatever. But we can get around all that by disallowing these duplicate rows!

Fortunately, this is fairly simple to achieve in a database schema by adding a unique index on champions.tool_id and champions.member_id. We can do something similar in our Alloy model by introducing a fact (a logical statement that Alloy will assume is always correct.)

fact "a unique index on champions prevents duplicate member+tool combinations" {

all t: Tool, m: Member | lone c: Champion | c.tool = t and c.member = m

}

In English, this is saying "for every combination of Tool and Member, there's at most one Champion that connects them." (The mnemonic for lone is "less than or equal to one". In this case, you can think of it as "if there's one, there's only one.")

Just to emphasize, Alloy will take our word that this fact is always true in our system instead of checking it for us! Because of this, I like to include some justification in the description for how this is true in the system I'm modeling. In this case, that means explaining the mechanism for how we're going to make sure this property holds: the unique index.

To make sure we've got this completely covered, we'll also assert that we solved the problem. In this case, we'll assert that the case we found earlier can't come up because of our new fact:

check NoDuplicateChampions {

no disjoint c1, c2: Champion | c1.tool = c2.tool and c1.member = c2.member

}

We need disjoint here because, otherwise, Alloy could choose the same Champion as both c1 and c2, in which case the assertion would be trivially disprovable—two references to the same champion would naturally have the same tool and member.

Alloy does not find any counterexamples to this check, so we're safe to continue.

Trainings

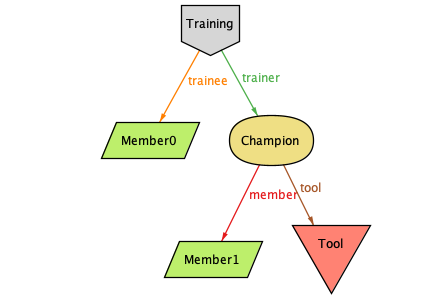

Now that we have champions members to join the space, tools for them to use, and champions to train them… how do we get access to the tools? Trainings! Someone can have access to a tool that they've trained for, so we can represent it as another sig/table:

sig Training {

trainer: one Champion,

trainee: one Member,

}

We'll add another validation, as well: that the trainer and trainee can't be the same person. We may be able to do some index trickery to get this to work, but I think it's more likely that we'll have to validate this at the app level.

fact "the application code validates that trainer != trainee" {

no t: Training | t.trainer.member = t.trainee

}

Including this justification makes me wonder what the application should do if someone inserts a row that violates this fact into trainings directly, but I'm going to leave that for the moment.

Examining More Instances

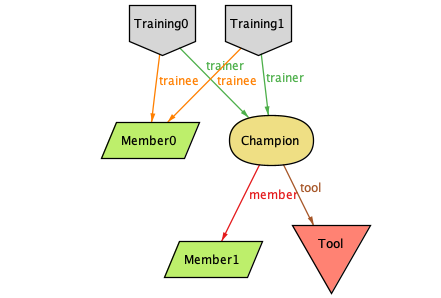

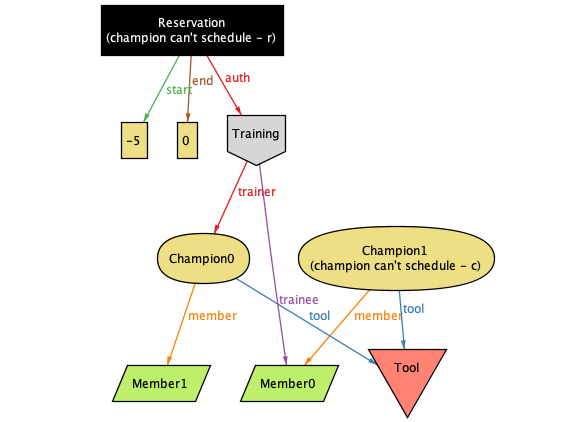

Let's look at the model instances to see if there's anything worth fixing now. Fortunately, there's not a lot: we've already ruled out quite a few problems with our modeling so far. That means we'll get mostly "normal" instances. For example, here's what it looks like when a champion has trained someone on a tool:

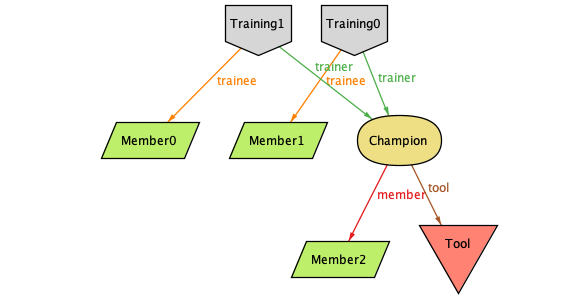

A champion can also train two members on the same tool. Also fine:

But Alloy also gives us this, in which the same member is trained multiple times:

Thinking through our domain, this might be ok. Because the training is for safety, it's not uncommon for someone to request to have a refresher on a tool if it's been a while since they've used it. This is especially common with the woodworking tools, where there are a lot of sharp things near your hands. However, is it OK in our database schema, or would we rather disallow duplicates and (for example) update the date of the training if someone re-trains? I'll have to talk to the person in charge of our current record-keeping system to find out!

Reservations

We've already found a couple of interesting questions in our modeling; let's see if we can find more by modeling reservations on machines (finally, we get to the reason I'm doing this in the first place!)

sig Reservation {

start: one Int,

end: one Int,

auth: one Training,

} {

-- a CHECK enforces ordering in the database

start < end

}

We'll use Ints to specify the start and end times of the reservation and specify that they have to be ordered. One weird corner I'm noting about this design is that since I've used Training as the authorization (just to say that you can't get time on a tool you haven't been trained on) you have to access the tool in a roundabout way: given a Reservation named r, it's r.auth.trainer.tool. Could be worse, but that's gonna be a lot of joins in the database. There are a couple of alternatives here:

- we could reference

Tool directly from Reservation, but then we could then construct a Reservation for a tool that a member hasn't been trained on using a Training for another tool. We'd have to enforce that in the app, and I'd prefer not to—the database should take care of data integrity, where possible. - we could embed a

Tool in Training as part of the foreign key to Champion, then do the same in Reservation. This would be a bunch of coordination work, but might be nicer: it'd mean that we couldn't change Champion.tool without figuring out how to update Training and Reservation at the same time. It'd take more coordination, but it'd give our data model some nice additional robustness.

I'm partial to adding the foreign keys from option 2, but for the sake of completing our model (and this post) let's move on.

Preventing Conflicting Reservations

To finish the reservations table, we should rule out overlapping reservations for the same tool. To start with, we can assert (incorrectly) that reservations already can't overlap to get Alloy to give us a counterexample:

fun reservedTimes[r: Reservation]: Int {

r.start.*next & r.end.^prev

}

check NoConflictingReservations {

all disjoint r1, r2: Reservation |

r1.auth.trainer.tool = r2.auth.trainer.tool

implies no reservedTimes[r1] & reservedTimes[r2]

}

The way to read this is "given two different Reservations with the same tool, there should be no overlap in their scheduling." The implies there works like a conditional statement in an imperative language: in this case, you can read it as "if X then Y" instead of "X implies Y," so "if the tools are the same, the times can't overlap."

The next and prev relations on start and end are new as well—they come from Alloy's ordered set support and implicitly exist on ordered sets like Int. They let you do things like calling 1.next to get 2. You can use the recursion operators here (another new concept to us,) where * will repeat a lookup zero or more times, and ^ will repeat a lookup one or more times. That means that calling r.start.*next gives us r.start plus all the times after it, and r.end.^prev gives us all times before the end, not including r.end (since one reservation should be able to start exactly when another ends.)

If we find the set intersection of those two lookups (the middle of a Venn diagram), we get a range, so saying r.start.*next & r.end.^prev gets us the range of reserved times for r. We can use this (in reservedTimes) to make assertions that there's no overlap between the two reservations.

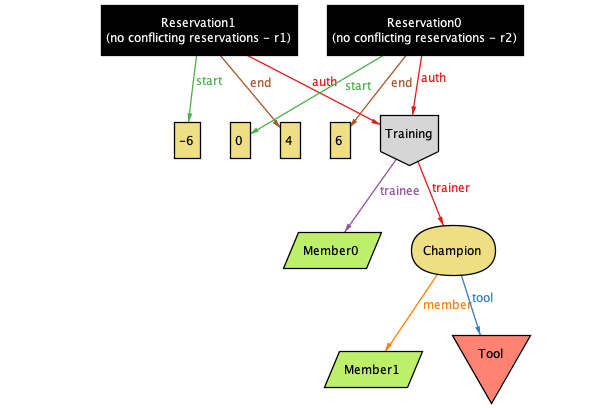

As expected, Alloy finds a violation of this check more-or-less instantly:

In this case, the same member is making both reservations. I'm not convinced that that's OK, but we'll leave it alone for now and focus on the fact that r2 starts at time 0 before r1 ends at 4. It looks like we can use a GiST index in PostgreSQL to exclude overlapping ranges. In fact, the last example on that page shows how you can avoid conflicts for a meeting room, which is similar to our example!

So, for now, let's introduce a new fact with the constraint that would be introduced by adding such an index:

fact "a GiST index prevents overlapping ranges" {

all disjoint r1, r2: Reservation |

(r1.auth.trainer.tool = r2.auth.trainer.tool and r1.start <= r2.start)

implies r1.end <= r2.start

}

We only have to make one assertion here (that r1 ends before r2 starts) because Alloy will check every possible combination of Reservation (that's what all does.) That means that every reservation will eventually be checked as both r1 and r2.

Anyway, Alloy now says that it can't find any counterexamples, which is what we want.

Browsing Instances Again

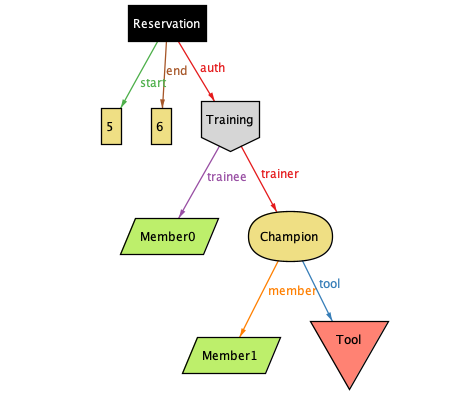

I think we're done now, but I'm just going to browse a couple more examples to make sure. (I do this a lot.) First, we get a completely normal reservation:

No conflicts and the structure looks OK to me! Next, we have one reservation starting as soon as the previous one ends:

This one's a little funny since someone is using two different training authorizations. This is the kind of example I'll have to bring up when I talk with the person who keeps the records now. Having a diagram like this can help explain the case I'm thinking about to someone else, so I'm glad I found it. I'm also going to ask whether it's OK for one member to have two consecutive reservations—I don't know!

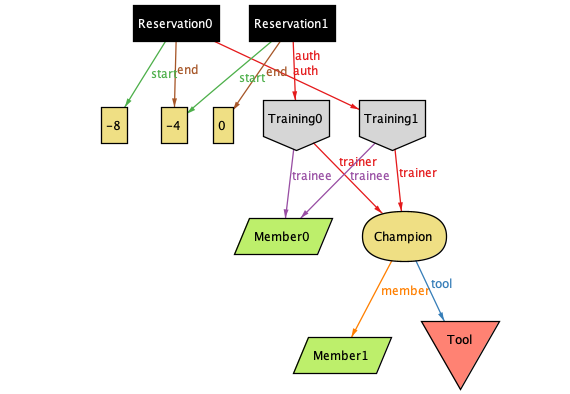

I also notice we're not getting any instances where the champion can schedule a reservation, but that's something that should be able to happen. We can get Alloy to show us if it's possible or not by asserting it can't happen and then looking at the counterexample:

check ChampionCantSchedule {

no c: Champion, r: Reservation | r.auth.trainee = c.member

}

Alloy comes up with this. A champion can be trained by another champion, at which point they can make reservations.

That seems reasonable, but how do you bootstrap it? Maybe Champion actually needs to be a subset of Training (that is, a boolean field on the training table?) Or maybe we should relax the requirement that a champion can't train themselves? This is an edge case that I might not have thought of otherwise!

But let's leave this here for now. With only a page or so of Alloy code, we've chased out a bunch of potential bugs in our model and found some interesting jumping-off points for questions while I continue to develop the model into an actual application. This has been pretty typical of my experience using Alloy in this way: in all but the simplest cases, it finds questions that I need to answer with very little effort on my part.

Hopefully, at this point, you're interested and want to learn more about Alloy. Here are some good links:

In general, most learning material does not cover Alloy 6, which came out about a year ago as of this writing. The links above are the only things I've found that do, although there may be more by the time you're reading this!

Thanks to Hazem at the Recurse Center and Tessa Kelly at NoRedInk for reviewing drafts of this post!